The Guthlac Roll an Introduction

The Guthlac Roll is one of the most curious manuscripts to have survived from medieval Britain. A series of lively images runs from left to right across its length illustrating the life and death of St Guthlac. Made almost 800 years ago (but 500 years after the events it depicts), the pictures on the Roll can be dated to the thirteenth century when Saint Guthlac’s shrine at Crowland Abbey was a popular destination for pilgrims. We do not know who illustrated the Guthlac Roll but it was probably made in the area of Lincoln around 1210.

The Life of Saint Guthlac

No more than 35 years after Guthlac’s death in 714 AD, King Ælfwald of the East Angles commissioned a monk called Felix to write an account of the saint’s life.

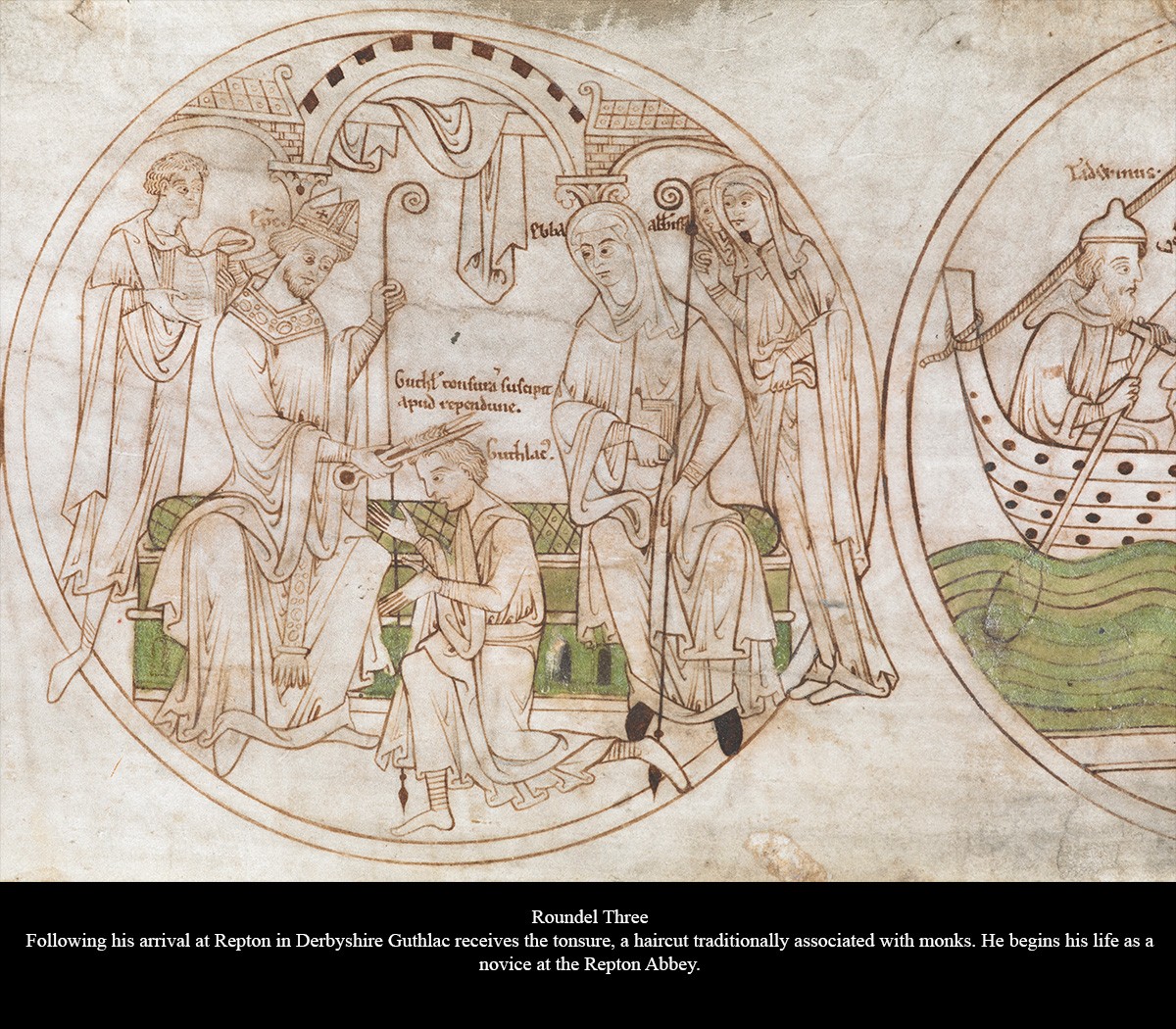

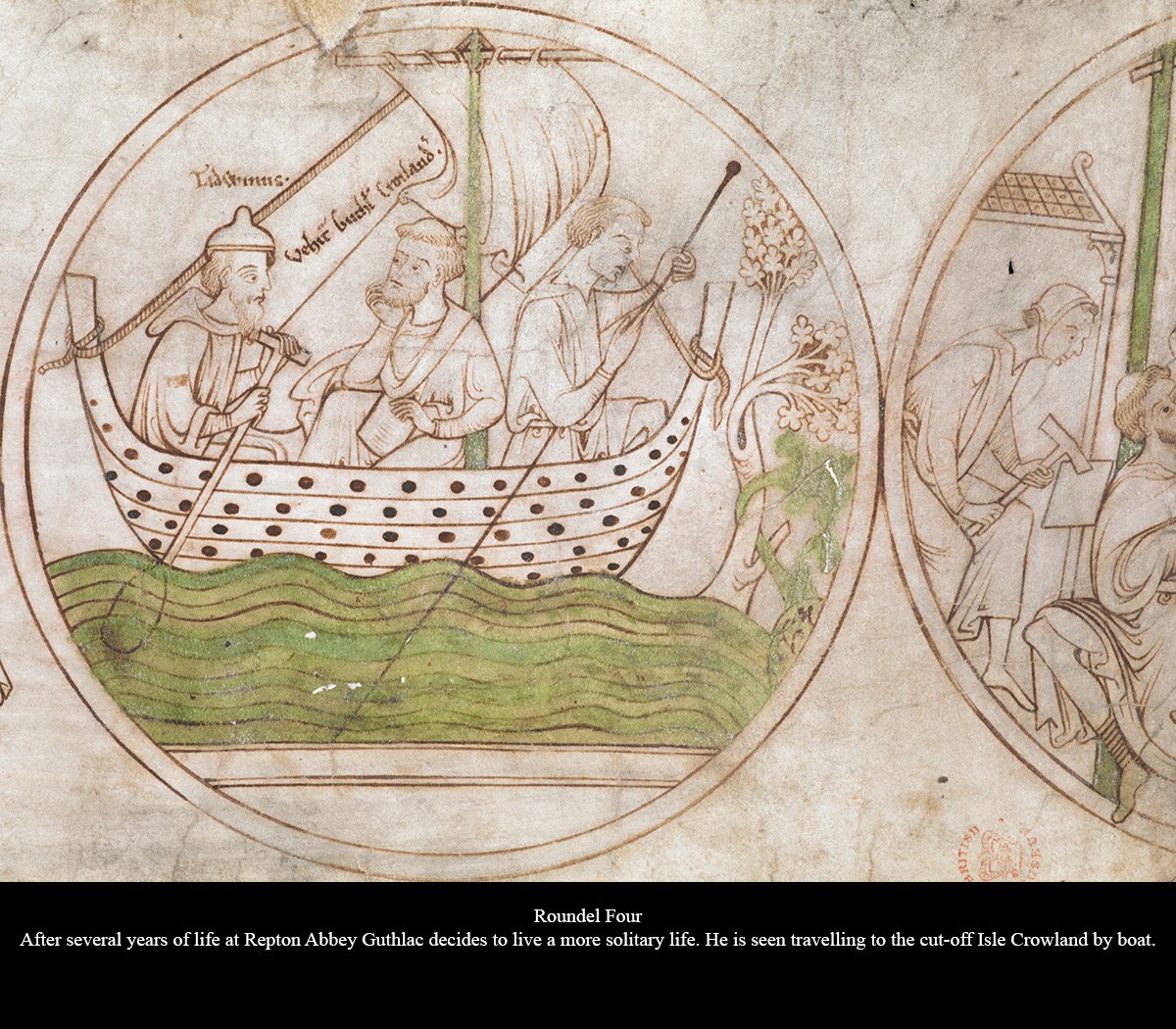

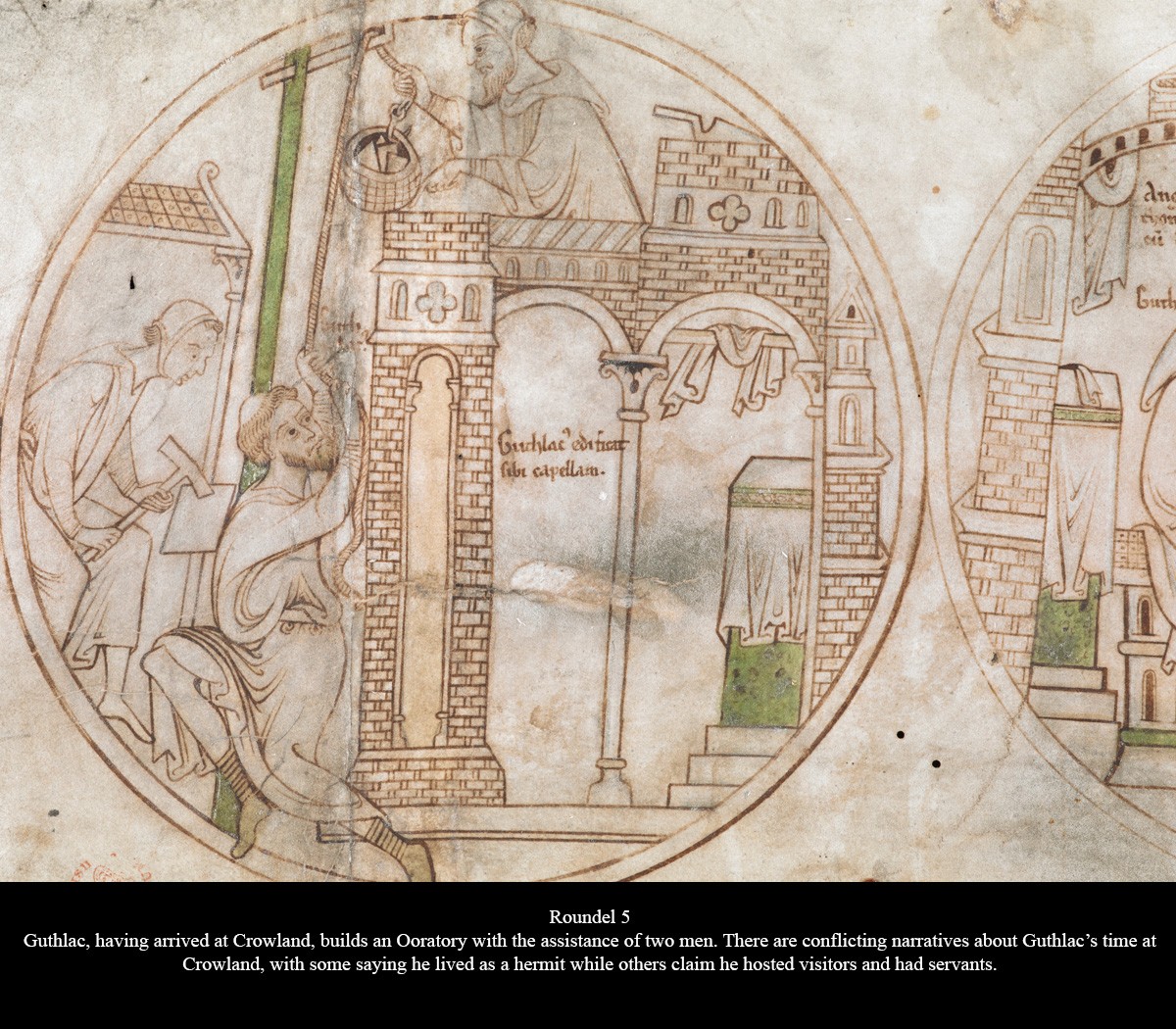

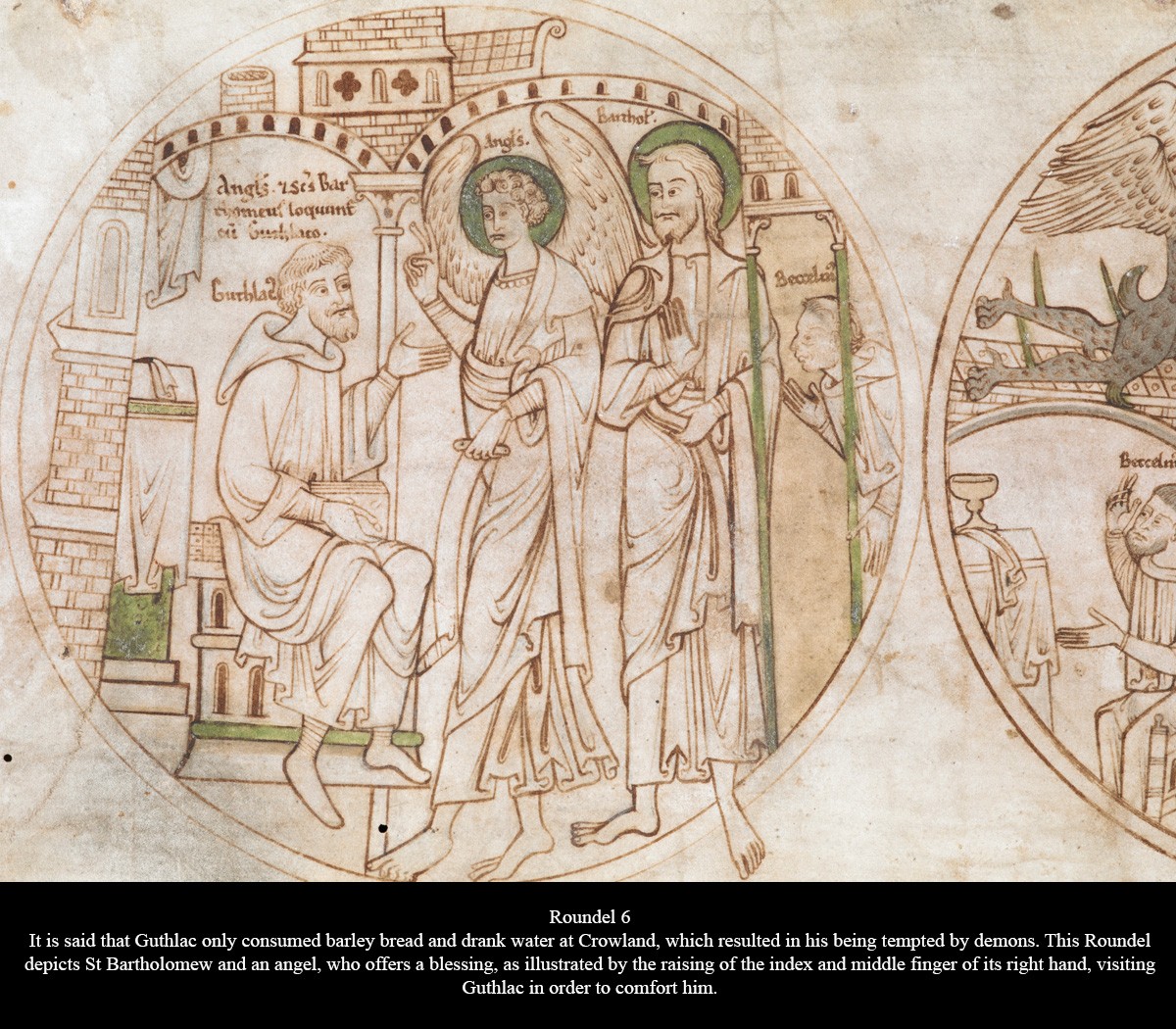

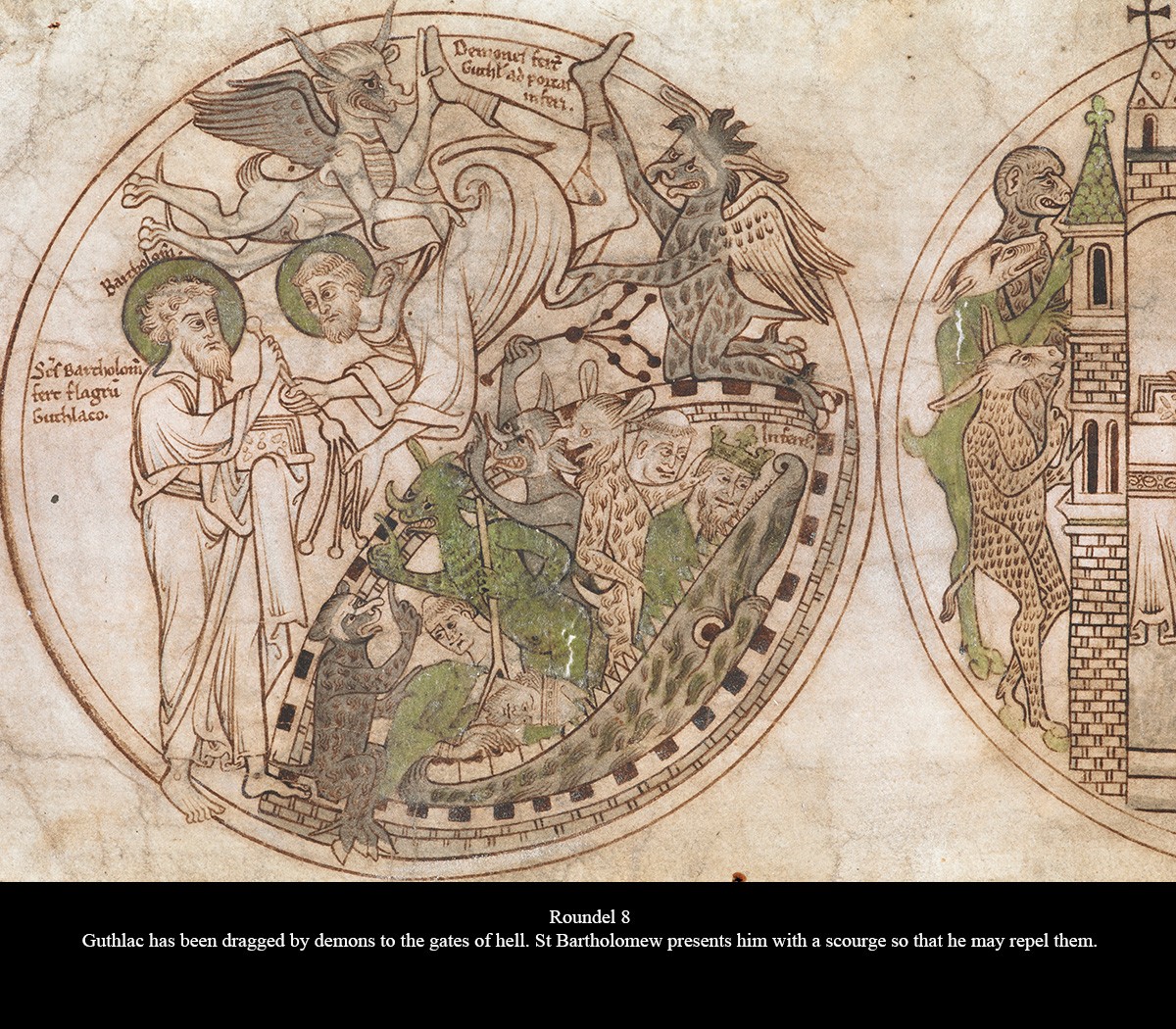

Born into a noble family in Mercia, a great Anglo-Saxon kingdom centred on the area of the English Midlands, Guthlac was inspired by the deeds of his ancestors and formed a band of soldiers. At the age of 24, he experienced a profound conversion and entered the monastery at Repton in Derbyshire. Soon gaining permission to live a solitary life as a hermit, he chose a remote and desolate location on the island of Crowland, like Christ in the desert, Saint Anthony in the wilderness, and Saint Cuthbert on the Farne Islands. He arrived on the feast day of Saint Bartholomew (24th August).

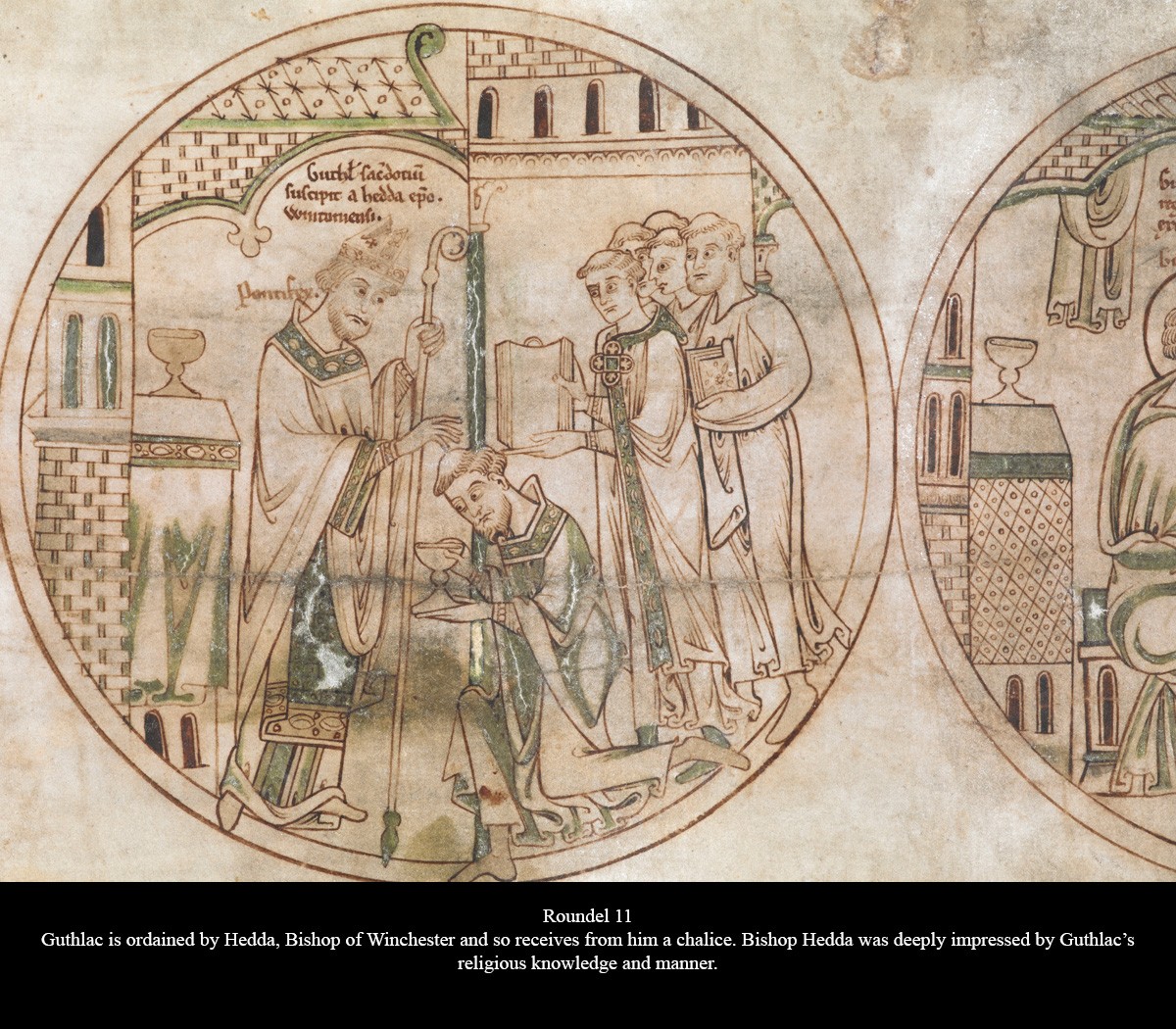

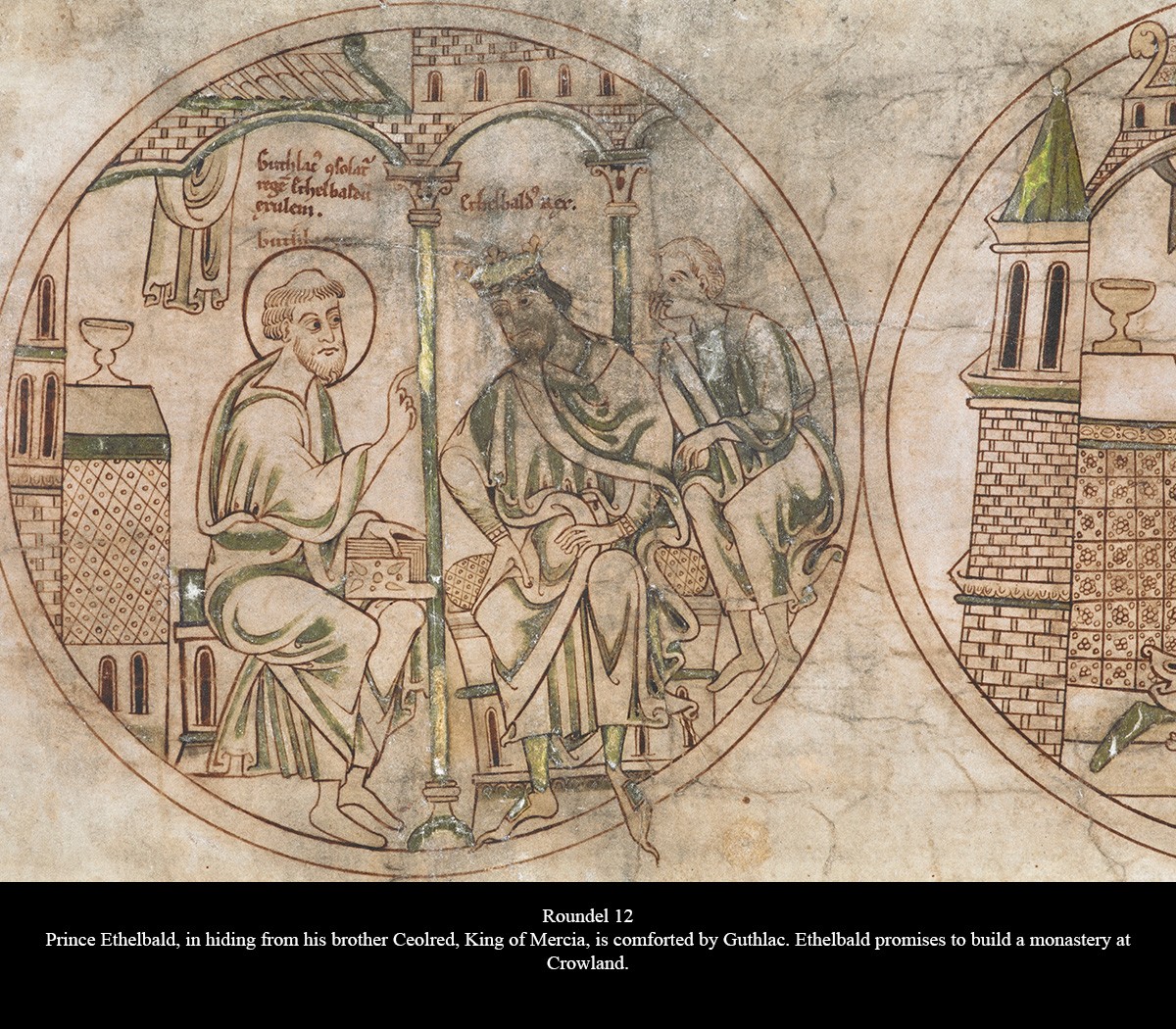

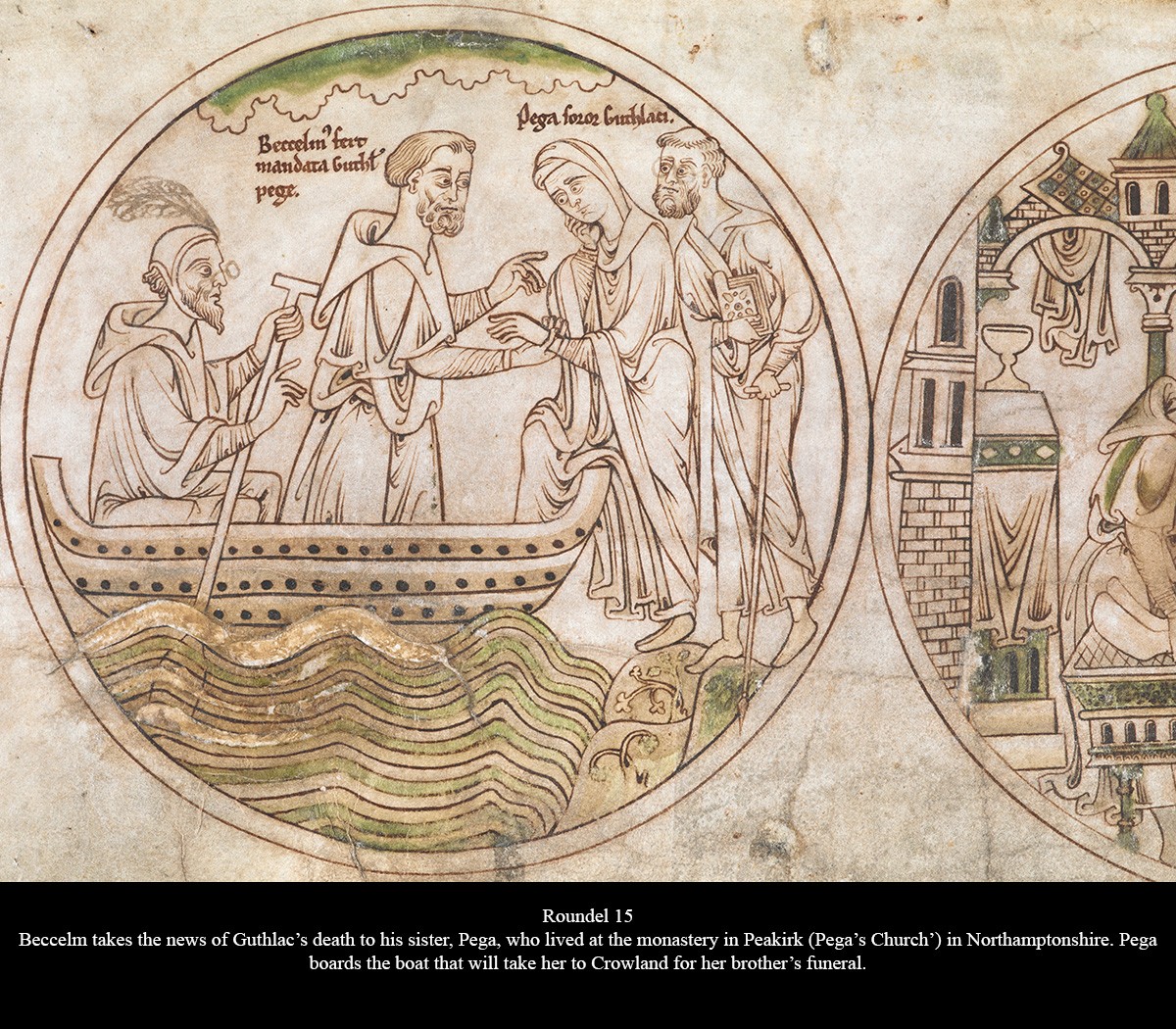

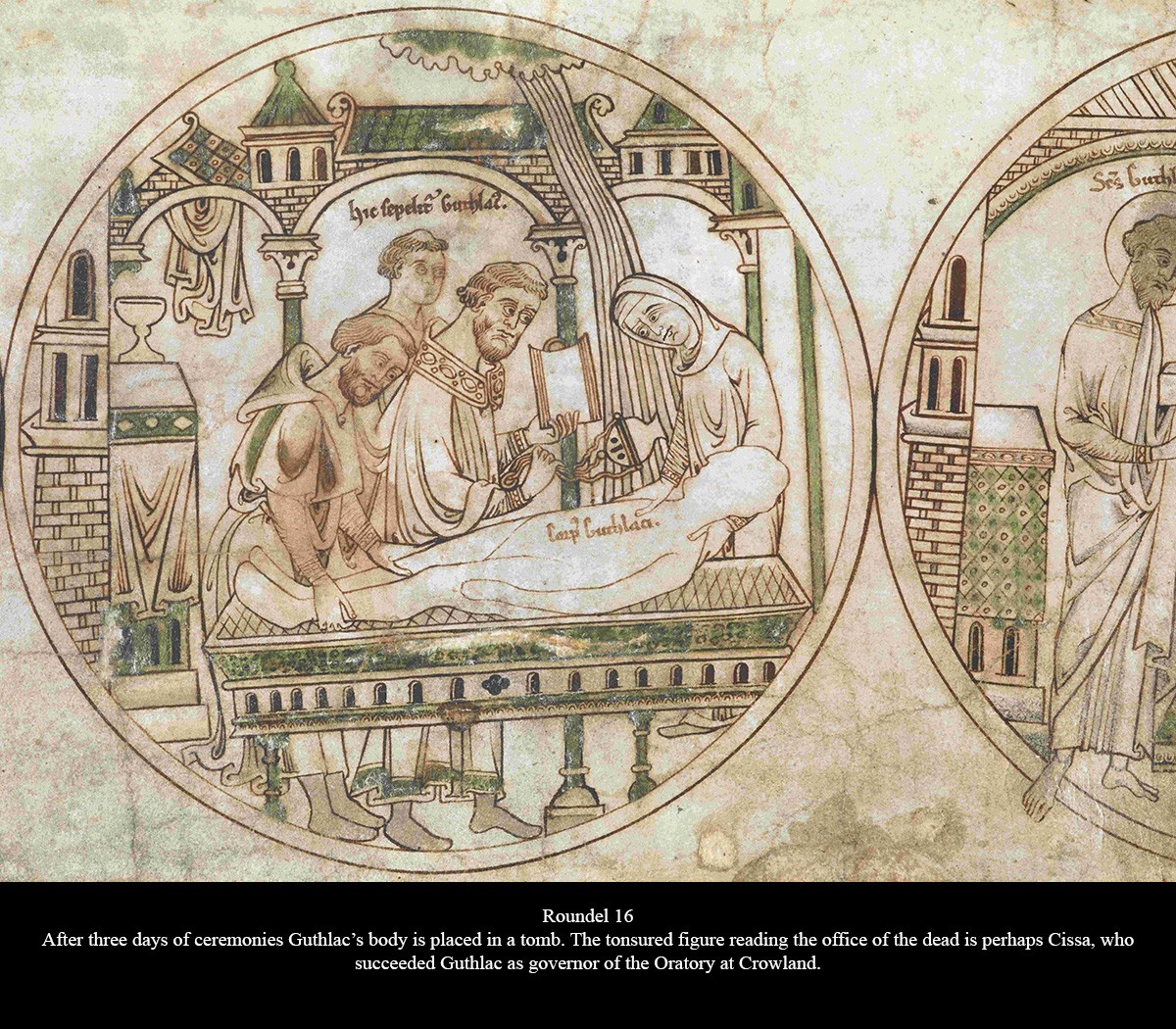

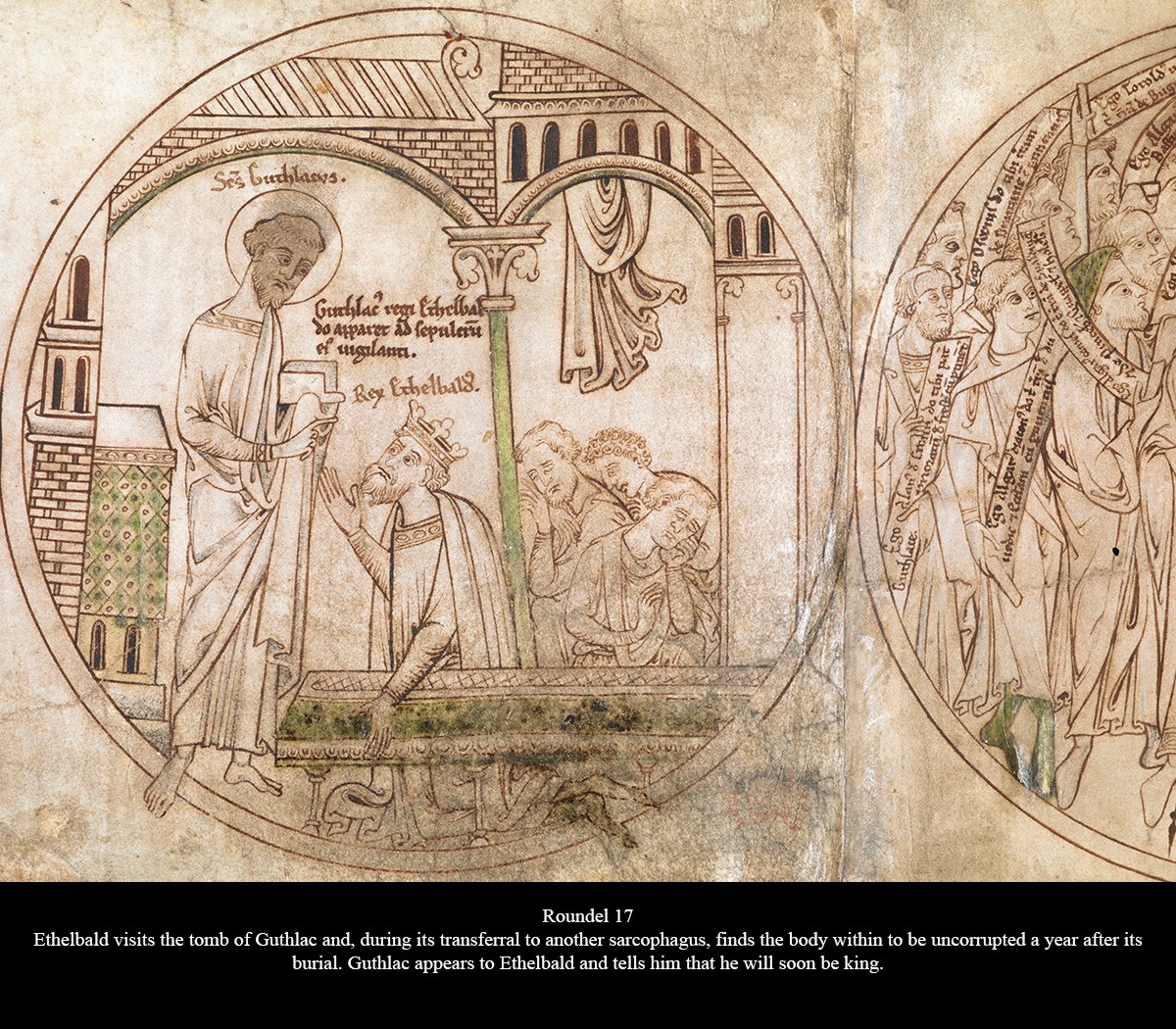

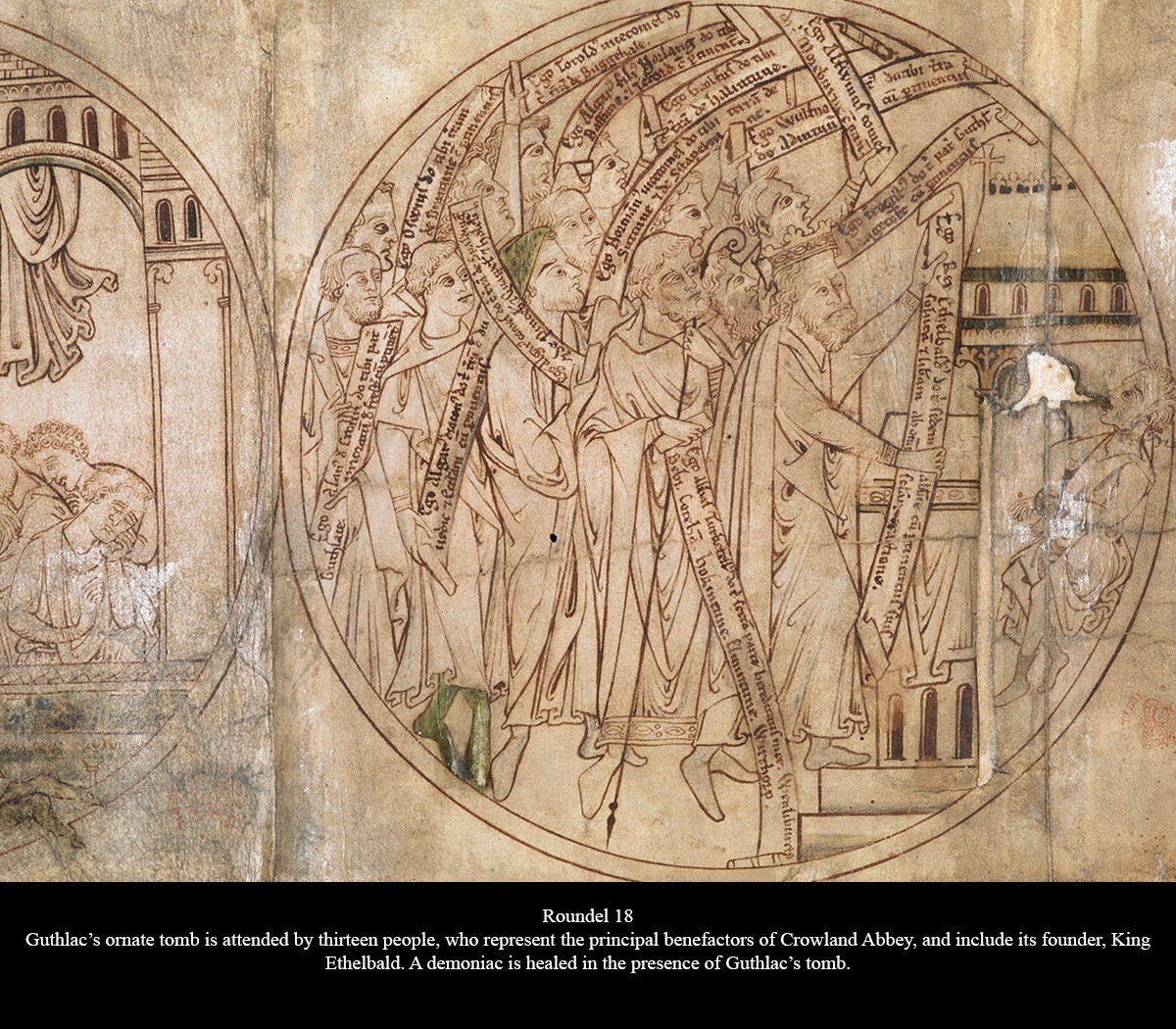

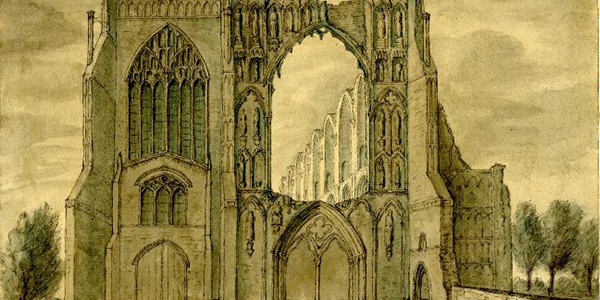

Guthlac was elevated to the priesthood and gave spiritual counsel to his kinsman Æthelbald, a claimant to the throne of Mercia. Foreseeing his own death, he sent for his sister who buried him. A year later Æthelbald returned, this time as king, and on finding Guthlac’s body miraculously incorrupt in its tomb, he built a monument to honour the saint. A number of different versions of Guthlac’s life developed over the succeeding centuries. The Guthlac Roll is one of the two pictorial versions to have survived. The other can be seen carved in low relief within a quatrefoil-shaped frame on the west façade of the abbey.

Guthlac Roll with kind permission of the British Library.

The Manuscript

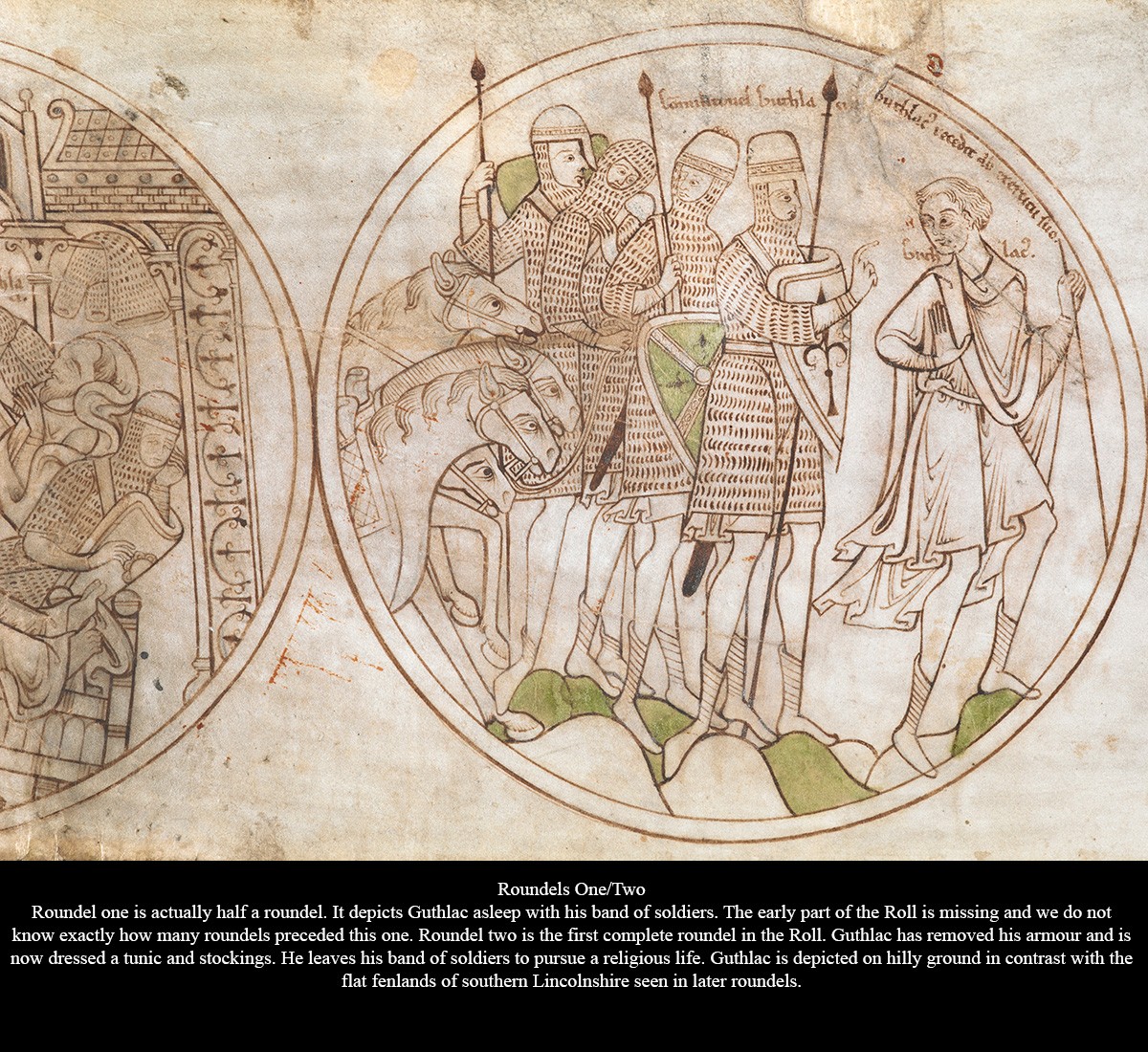

Nearly three metres long and seventeen centimetres wide, the Guthlac Roll gives a unique account of the important events in the life of the Crowland saint in eighteen circular pictures, or roundels. This is very unusual. Most manuscript versions of saints’ lives are books not scrolls, and the pictures are usually in rectangular frames or a grid like a comic book. For these reasons, people have wondered if the Roll was actually a plan for something else where sequences of round pictures are more common. Could it have been for a stained glass window? Or maybe it was for sculpture, like we see over the double doorway to the right of the west door of this church?

Unfortunately the part of the manuscript that might have told us is missing. The beginning is damaged and we do not know when this happened or how much of it is gone. The story now starts halfway through a night-time scene, probably the moment when Guthlac decides to devote his life to the Christian faith.

We can only trace the history of its ownership back to the seventeenth century when it belonged to Sir Robert Bruce Cotton (1571 – 1631). After that it belonged to members of the Harley family until it was sold to the nation in 1753. The Guthlac Roll is now preserved in the British Library.

Deciphering the Pictures

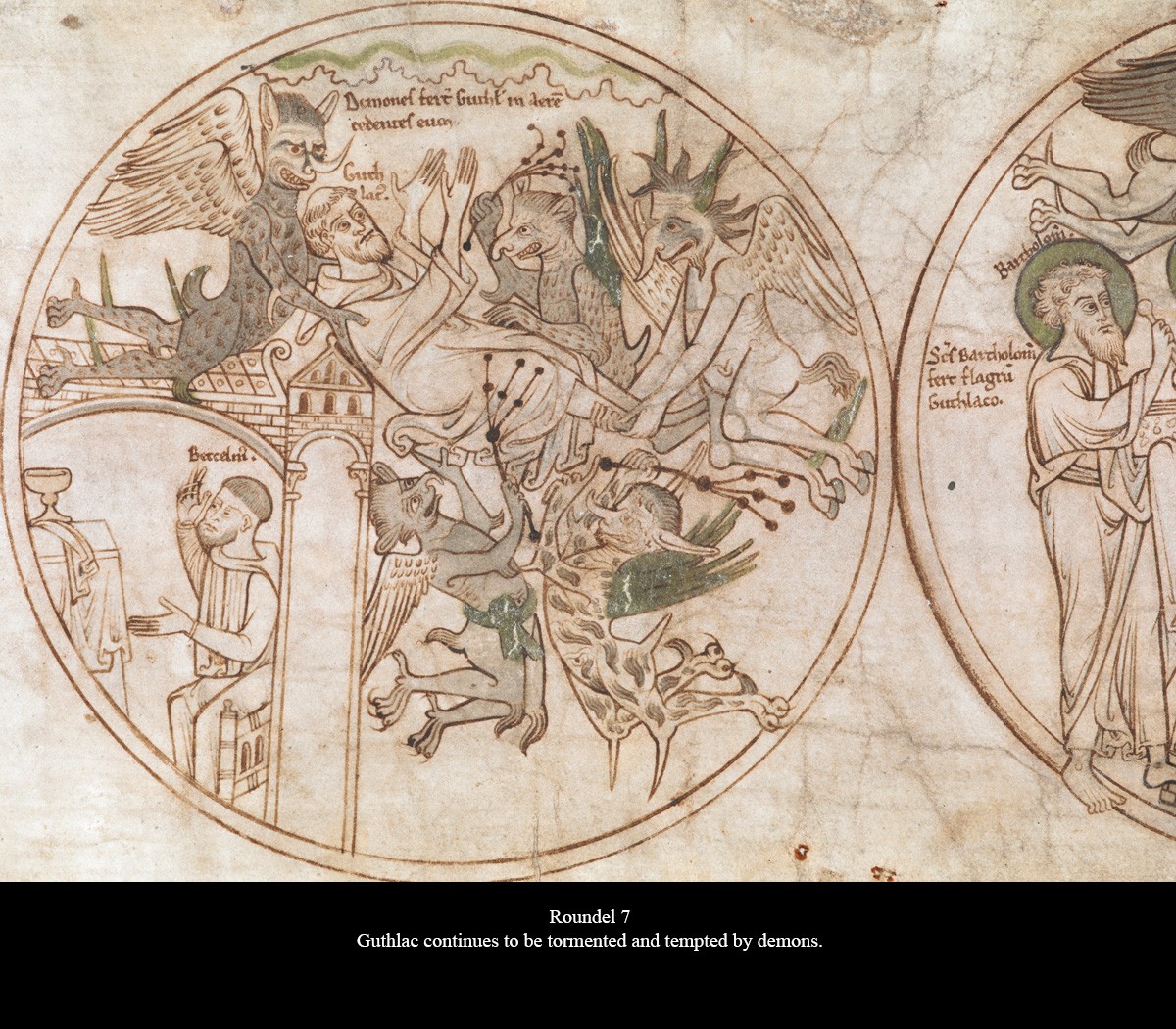

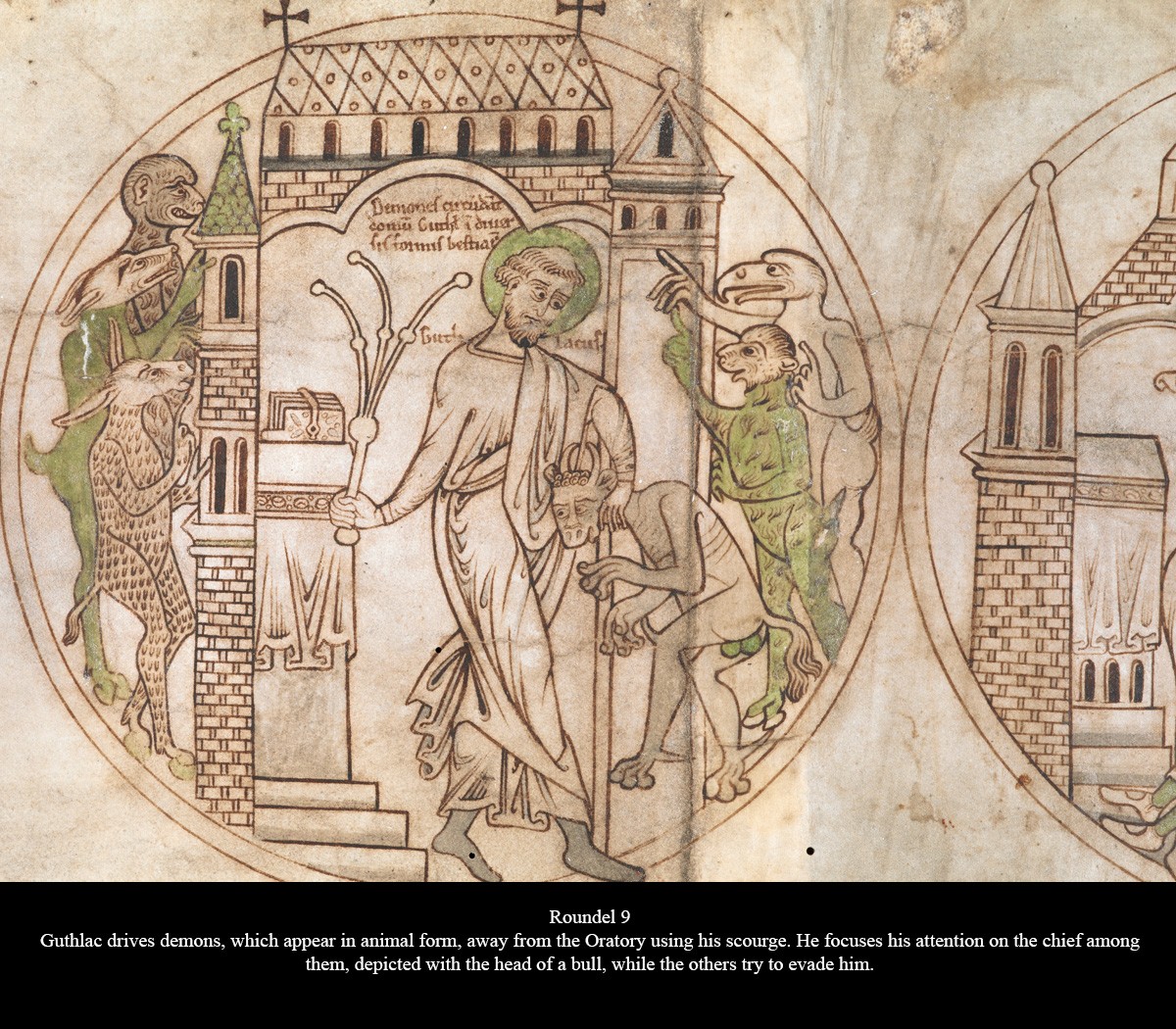

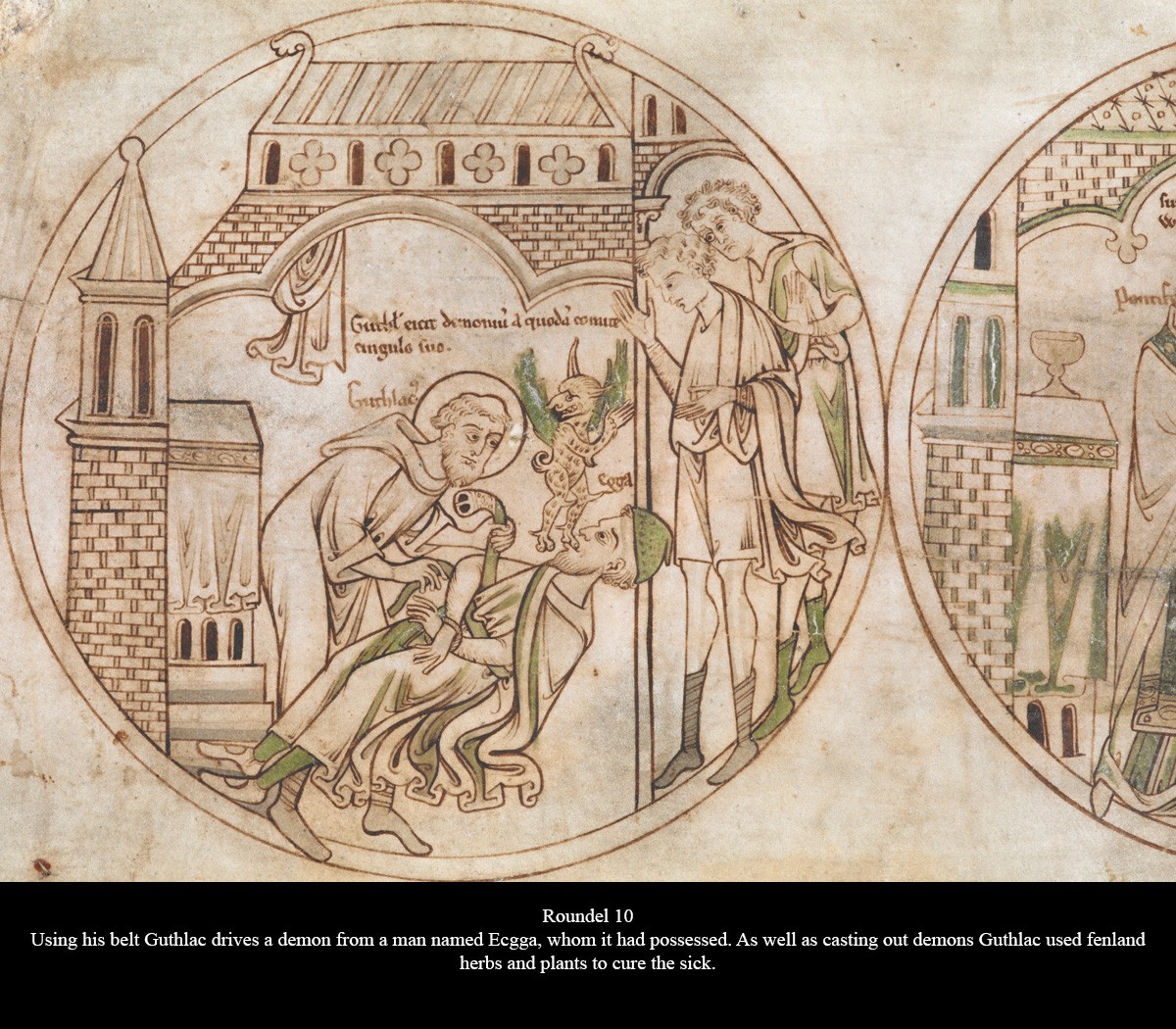

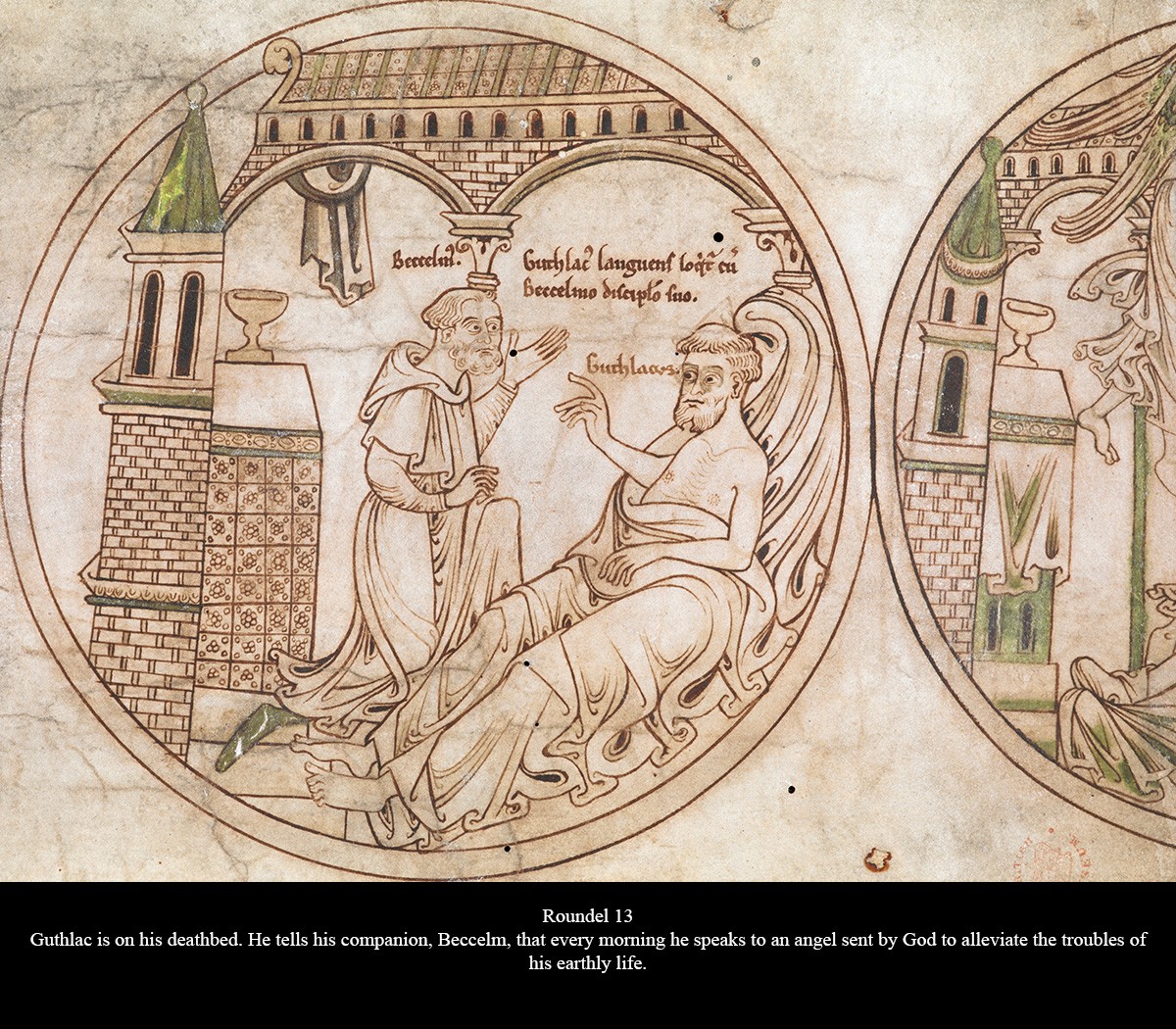

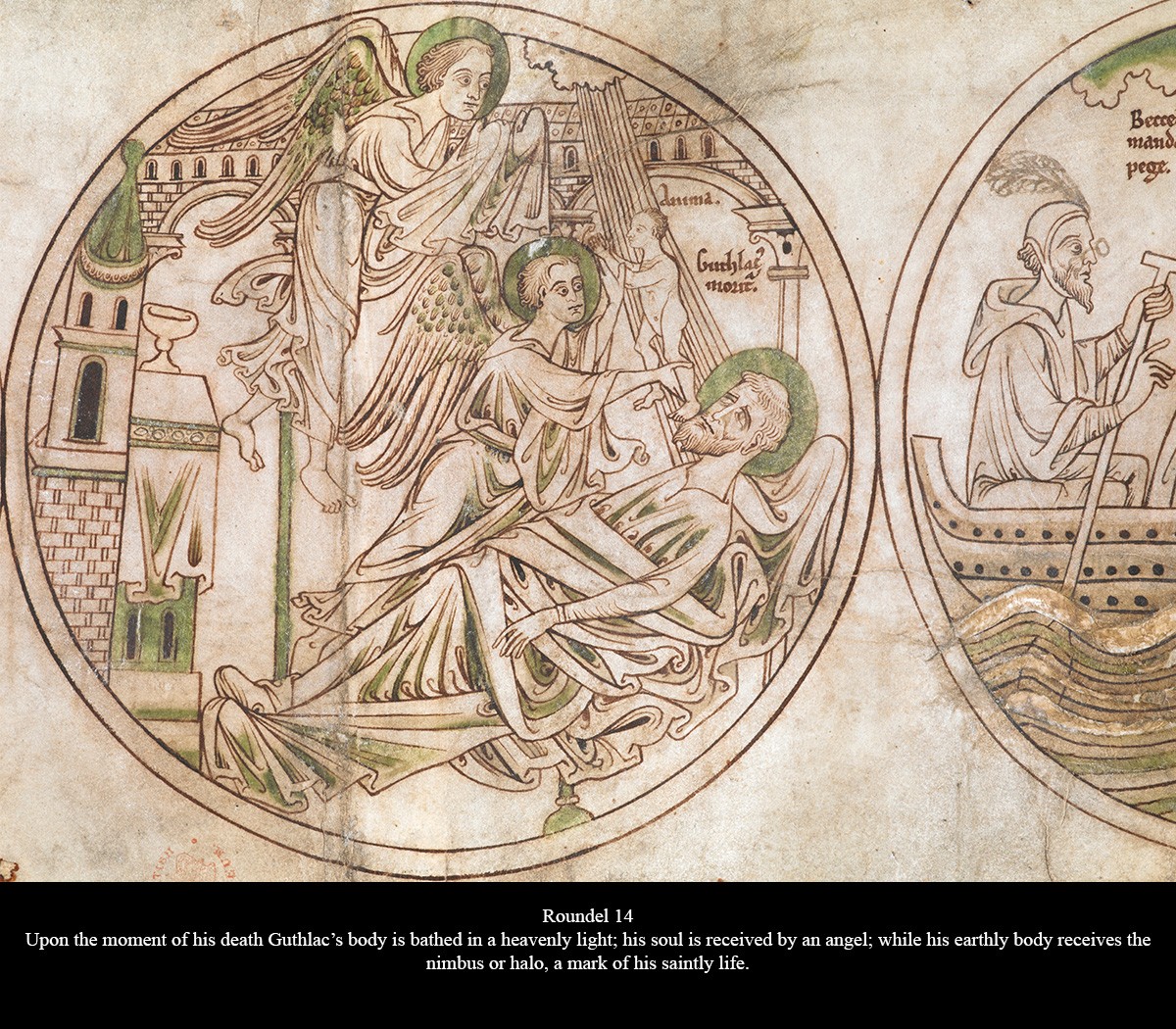

The eighteen surviving scenes describe the major stages in Guthlac’s life: his calling, the testing of his faith, his service to the church, and the signs of his holiness before and after death. Each picture is a separate moment in time. No character appears more than once in the same scene, but can reappear several times across the length of the Roll if they are involved in the action. Guthlac’s death is presented in two separate pictures even though the location is the same and not much time has passed between them. First Guthlac gives instructions on his deathbed. Then his body lies rigid and lifeless as an angel receives his soul. The pictures read from left to right, and the action moves in this direction as well. When the young Guthlac leaves his war band to join a monastery, he is shown walking away from his companions on the left towards the next picture on the right.

Inscriptions in Latin help identify some of the characters and action, but it is up to the viewer to interpret the scenes. To begin to understand the pictures, it is useful to know what to expect. Some ways of drawing things are still familiar to us now. Large areas of water are represented by wavy lines. Buildings sometimes look sliced in half so you can see inside when scenes take place indoors. Angels have wings and their feet are bare. However, that none of the characters ever open their mouths to speak is more surprising. Talking in medieval art is usually indicated by a raised index finger instead. Once you know what to look for, you can start to read the pictures on your own.

Dr Rosie Mills, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

How it was Made

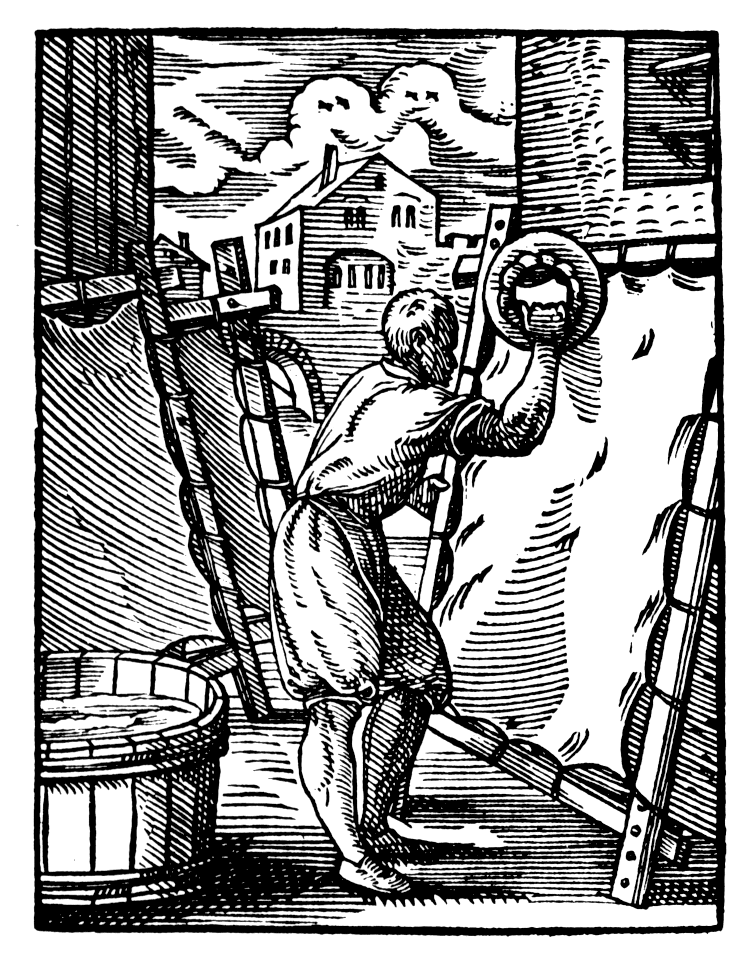

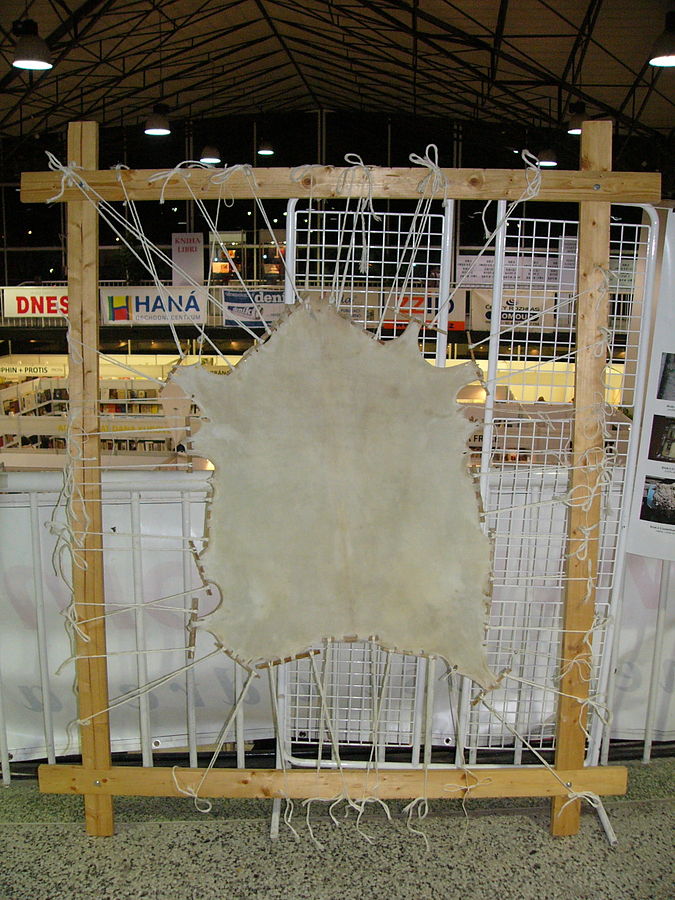

Several long strips of parchment were glued end to end to form the Guthlac Roll. Parchment is a general term for the sheets made of animal skin used for writing and drawing throughout the Middle Ages, and still used today. Calf, sheep and goat skins were the most commonly used. The skin is first cleaned and all the hair removed before it is stretched on a frame to dry.

When the skin is completely dry, it is cut into sheets and ready to use. Each strip of parchment in the Guthlac Roll is a different length.

The pictures are drawn in black ink and tinted with light washes of green and yellow. The ink was made with tannic acid extracted from the large round growths found on oak twigs called galls.

This is the best type of ink for parchment because it bites into the animal skin. The ink was applied with a goose quill pen. Feather quills from the left wing were preferred because they curve away from the face when held in the right hand.

It is continually tightened on the frame and scraped as it dries, removing all remaining fat or flesh from the inner side and hair from the outer side. A curved or crescent-shaped blade is used for this job because the skin gives a little under the pressure of the tool and is easily torn by the ends of a straight blade.